Filed under: Codes & Regulations, Volume 003 | Tags: Architectural Code, Design Guidelines, Historic Districts, Ian Rasmussen, Landmark Commissions, Law, Preservation, Regulations, Zoning

By Ian Rasmussen

“[I]t is essential for the city to have confidence in new buildings as well and to know how to do it correctly in relation to the old.” — Vincent Scully, Jr.

Being designated a “historic district” is perhaps the greatest honor that can be bestowed upon a neighborhood. More often than not, what is being recognized is not the significance of historic events having occurred there, but that the neighborhood has a defined style and sense of place which contribute to our culture. This got me to thinking: Will Seaside—dubbed the most astounding design achievement of its era—ever be a historic district?

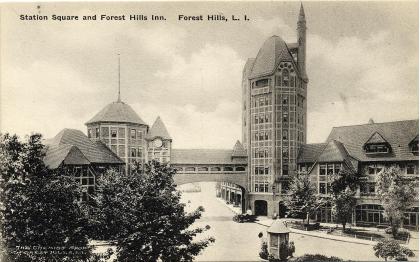

One place to look for an answer is at great planned neighborhoods from the past. Interestingly some, such as Boston’s Back Bay or Brooklyn’s Park Slope are historic districts; others such as Queens’ Forest Hills Gardens, or Kansas City’s Country Club district are not. The difference between them is that the latter are subject to architectural regulations and therefore do not rely upon historic preservation laws to protect them. Similarly, Seaside and most other new urbanist communities are subject to architectural regulations which served to define, and now maintain, their style. To be sure, the advancement of such codes is one of the most remarkable achievements of the new urbanism.

The fact that places like Seaside, or Forest Hills Gardens, can maintain a consistent and excellent architectural style without the aid of landmarks commissions, public hearings, and what is a whole other layer of regulation and administration, is not without significance. There are a number of values promoted by new urbanism that are furthered by the use of architectural codes, as opposed to preservation laws: for example, making the approval process swift, and its outcome more predictable.

From this writing, I have concluded that the question of how a City instills confidence in new buildings comes down to two central promises. First, that what we build will be better than what it replaces. There are really only two good reasons to knock anything down: it’s about to fall down, or you are going to replace it with something better. Whether old-growth trees or a grand building, so long as the replacement is more valuable, it is progress. Historically this is how we built. No sooner did we break this promise than did NIMBY-ism rise up and force us to spend our evenings being cross-examined at community meetings.

Second, that the more complex and imposing our regulations, the more swift and certain their administration. Tell people they can build whatever they like so long as the Town Board approves, and the process is at once flexible and indefinite. But, tell someone how tall, how wide, what color, and what type of windows their building must have, and they should be able to reasonably assume that if they meet your list of demands, they will be allowed to proceed.

Replacing the laws and approval processes of historic districts with architectural codes offers to fulfill both those promises, and improve the system along the way. Before explaining why, and to fully understand why the status quo isn’t the best solution, it’s useful to examine the problems historic preservation laws were invented to solve.

Background

The half-century from 1920–1970 bore witness to a stunning degradation in the quality of American architecture. Though the profession’s work had arguably peaked at the turn of the twentieth century, it really declined during this period. The reasons for this fall from grace are many, too numerous and complex to fully discuss. But, at least a few help put the rise of historic preservation in context.

First, the era of modernism and the “International Style,” borne of European architects and theorists in the 1930’s, materialized and became fashionable in the wealthiest, most advanced nation in the world: post-WWII America. Second, the influx of high-skilled, cheap labor (almost constant from 1860–1910) that allowed complex buildings to be economical dried up as immigration policies changed leading into the Great Depression and WWII. Third, the advent of the automobile, and the massive government subsidization of our transition to a way of life that revolved around it, stacked the deck against buildings and developments that did not accommodate the car.

Finally, and most importantly in my opinion, was a cultural shift from focusing on the quality of buildings, to the quantity of buildings. The generation that experienced adolescence in the throes of the Great Depression, and early adulthood in the battles of WWII, inevitably had a different outlook on what mattered. They understood that everything could be taken from you in an instant. They saw that all the grandeur of Paris or London could be bombed out tomorrow. It’s only natural they rebuilt as quickly as possible, and without regard for the ornamentation of buildings.

It was the perfect storm for the destruction of America’s older buildings. By the end of the 1940’s they were out of style, too expensive to repair, didn’t have enough parking, and were generally uncared for. And so we started knocking them down—a lot of them.

All of the great destructive trends in American history had a straw that broke the camels back: water pollution had “Love Canal”; endangered species had the Bald Eagle. For Historic Preservation, that straw was Penn Station. You could hardly have picked a better poster child. Penn Station was one of, if not the single grandest buildings ever constructed in this country. But as the railroads were being abandoned and dismantled, their stations fell into disrepair. For the Pennsylvania Railroad, which was struggling to survive, Penn Station was little more than a drag on its balance sheet. At the same time, under the newly adopted zoning regulations in New York City the site could be developed with over a million square feet of office space. To be fair, from a purely financial perspective it would have been foolish not to knock it down and sell the development rights for a new building. And that’s exactly what was proposed.

But it wasn’t just the building that made it so surreal and troubling, it was the entire episode. There was almost no opposition to the station’s destruction in the first place— protesters ranked not in the hundreds, or thousands, but in the tens. And the new station and the glassy office tower above it (which remain to this day) were simply dreadful. In case you haven’t been to the new Penn Station, the main entrance’s stairs descend to a concourse with nine-foot ceilings. As one critic famously said: “One used to enter the city as a king, now one scurries in like a rat.”

Though it is regrettable that such a tragedy had to occur, Penn Station’s greatest legacy will likely be as a catalyst for the historic preservation movement. In the years that followed, the loss of the station came to be nothing short of an embarrassment for New York; which soon after, in 1965, created a Landmarks Preservation Commission and began designating landmarks throughout the city. Realizing they had committed many heinous acts against their built heritage, other cities and towns across the nation followed suit.

The early success of the Historic Preservation movement, politically, culturally, and in the courts where its legality was confirmed, fueled its rampant spread. Not only among towns and cities, but within them, as diverse applications of “preservation” were experimented with. Obviously the first to be preserved were the landmarks, both historical and architectural—which more often than not do not overlap. Historical landmarks including buildings like the log cabin where Lincoln was born, and architectural landmarks including buildings like Grand Central Station.

Next came the advent of the “historic district.” Here things became slightly more complicated. Historic districts are composed of several buildings (typically several blocks, or even a whole neighborhood), most of which by themselves are not historically or architecturally significant, but which together form a place that is either historically important, or architecturally distinctive. You can imagine that if you weren’t able to protect any of Georgetown or Greenwich Village unless the buildings were independently or architecturally historic, those districts would be at risk.

The result is that now, the number of buildings that are protected elements of historic districts far outnumber the individual architectural and historic landmarks. To be clear, this essay doesn’t take issue with the system of landmarking individual buildings, but with historic districting.

The Existing Process of Historic Preservation

Now that historic preservation laws are virtually universal in this country, most of the important individual landmarks designated, and many of the important historic districts protected, allow us to focus on how (and if) the system works in practice. My involvement in, and perspective of, this process is as an attorney presenting applications to the Landmarks Commission; I mediate a debate about what should be built between the preservationists, the architects, and developers.

So you’ve purchased a vacant property in a historic district, or an old building you want to renovate or enlarge. How does the historic district constrain you? Generally, the answer is that in addition to presenting plans that conform to your local building and zoning codes (to get your permits), you need a separate approval from the landmarks commission (called a “certificate of appropriateness”). The only catch is that where the building and zoning codes are fairly clear in what is required, the idea of “appropriateness” is very vague. To be sure, there isn’t even a place where what it means to be appropriate in the historic district is defined. The solution is to visit the district, try to discern its common characteristics, and design something that emulates that style. Good architects, who understand urbanism, can design a contextually appropriate building on the first try. However, most architects learned to design without context in school, and design according to the bottom line in practice; the idea of context and precedent is foreign to them.

Here is how the rest of the story plays out: you present your plans to the landmarks commission; they say it’s not appropriate for this reason or that (all subjective opinions, mind you); the architect revises the plans; you present again; whereas last time the commission didn’t like the windows, now it’s the awning, or the entrance. This cycle repeats itself a few more times until the commission feels like they’ve gotten something out of the developer. The whole affair takes, and costs, about four times more than designing a building anywhere else in the city.

I love old buildings, and I don’t care for modern architecture, so I think I am as much a supporter of preservation as anyone; but there is something horribly wrong with this process. Though I’ve oversimplified it, and maybe even demonized the landmarks people in the process, that’s pretty much a fair telling of the system from my point of view. And, what’s really ironic is that most of the developers I work with are so eager to get the project done, they are willing to do almost anything the commission tells them to. Forget the archetype of the heartless developer; most just want to be told in clear terms, so they can tell their bank, exactly what they need to do for guaranteed approval.

The Approval Process with an Architectural Code

Now consider the experience of a person who has purchased a vacant lot at Seaside. Like anyone else, they want to know what they can build. The answer is found in the community’s urban code (which is like a zoning code), and architectural code. The entire document is a double-sided 11″ x 17″ sheet. What is appropriate in Seaside? A design that complies with its codes. Period.

Seaside, of course, benefits greatly from having a town architect to work with the owner and project architect to develop a compliant design. But even that is much less expensive, not to mention less cumbersome, than having an entire landmarks commission. If a design that is presented to the town architect is fully compliant with Seaside’s codes, it will generally be approved. How long it takes to develop a compliant design is up to the architect and owner; not a product of the process.

Again, I’ve simplified the whole process for the sake of discussion. And, I should mention that the ultimate discretion over what gets built in such place still lies with the town architect, even if the design is fully compliant. For the most part, though, that’s it.

Replacing Historic Districts With Architectural Codes

Not only are architectural codes a better tool to regulate new construction, but also development in historic districts. The advantages, though more plain in the case of new construction, also apply to older buildings. Before delving into why architectural codes are a better way to regulate historic districts, it’s important to understand why this is true.

We need to stop thinking of old buildings in historic districts as “historic buildings.” Historic buildings are places that are important to history. Old buildings in historic districts are just a part of historic places. These places can, with a tight architectural code, survive without all their original parts.

Consider why preserving historic districts became so important in the first place: people were knocking down beautiful old buildings and replacing them with garbage. If what was being constructed in place of the old buildings were newer, better buildings—architecturally, structurally, functionally and technologically—would we have minded in the first place?

Will many people knock down a beautiful old building when the only thing they are allowed to put in its place is a comparably sized, similar looking, new building. In fact, a good architectural code favors renovating or enlarging older buildings over demolition and new construction.

With regard to vacant properties being developed, there is no reason to believe that a new building developed under an architectural code will be any worse than one developed under a landmarks commission. Given the inability of such commissions to effectively communicate to the architects and developers, the code may even provide for better results!

The Advantages of Architectural Codes

There are numerous reasons why architectural codes are a better way to handle development in historic districts than the approval process of historic preservation. Maybe you hate big government, and the idea of one more layer of bureaucracy keeps you up at night. Or maybe you’ve been through the interminable process and endured hours-long public meetings at which the angry neighbors actually get a say in what you can build on your property. Ideologies aside, there are four specific advantages to using architectural codes.

The first is efficiency. Whether or not you think government should play a smaller or larger role in our lives, and whether it should shrink or expand accordingly, it’s fair to say no one supports waste—and the approval process of preservation is full of it. Think back to the hypothetical in the preceding section. The architect had to spend four times as long producing his plans; four times the paper, four times the pens, and so on. The developer also had to spend four times as much money. Everyone had to attend several public hearings. The commission has to be there, the project team needs to be there, and even the concerned neighbors had to take the afternoon off to be there, on several occasions. This is a waste of everyone’s time and resources. Not just the developers, but the municipalities and the citizens as well.

If there were an architectural code in place, how many of the gaffs in the early design proposals, and how many of the back-and-forths over them would have been obviated? How much closer would the architect’s first try have been to the final design? And, equally important, would it have been as good as what came out of the landmarks commission process? With a well-written architectural code, the answer is as good or better.

The second is objectivity. The law should be applied objectively. After all, why does the law prescribe how much you have to steal before its “grand theft” or how much pollution you can put in the air before you need a certain permit. You would not want to live in a world where whether you went to jail for two years or five depended on whether a commission thought what you stole was “grand,” or where your permitting requirements were subject to what a commission thought of your pollution. In virtually every corner of regulation, the law strives to reject these subjective opinions in favor of objective requirements.

The laws of historic preservation are a notorious exception to this general rule, mostly because it’s tough to codify style. Of course, this is what makes the issue one for the new urbanists; the group that has not only reintroduced the idea of architectural coding, but made great strides in the field. The bottom line is that in the absence of knowing a better way to regulate, the laws of historic preservation rely almost entirely on the subjective opinions of a few people. By comparison, architectural codes are almost devoid of subjective opinions, and rely on objective requirements, agreed upon by everyone at the outset, to get the job done.

A related advantage is the third: a dependable outcome. Not only with preservation, but with the public process, which dominates the field of planning, we completely got it wrong. Anyone who has ever applied to build anything—whether it’s a 10,000-unit new town or a backyard swimming pool—wants to know is what they are allowed to do. And what they are really getting at is not only what is permitted, but that if they comply with those requirements, it will be promptly approved. What’s been getting built since 1945 is basically so horrible that in most cases, and certainly any that are larger than a few buildings, we have decided there is no set of requirements that guarantee approval; we want to be able to veto anything. Historic districts are the epitome of this idea.

The problem is that this way of doing things runs contrary to one of the basic tenets of regulations: that the more complex and imposing the regulations, the more dependable their outcome should be. In other words, if you’re going to tell me exactly what I can build not only in terms of height and form, as with zoning, but also in terms of materials, colors, and details right down to the shape of the windows and their ornamentation; then I should be able to expect that you will make those requirements clearly known to me, and if I meet them, then I can proceed. That is basically what an architectural code does; it clearly defines compliance.

The approval process of preservation has the equation backwards; they not only want an intrusive degree of power, but they aren’t going to nail down a set of criteria to review against. Imagine, a legal process—and that’s what preservation is—where those in charge control almost every aspect of a building, but don’t have to you their requirements. In those terms it almost sounds despotic. A good deal of the resistance to historic preservation arises out of precisely this frustration.

Finally, and this may be the most important thing architectural codes have to offer, you to not need to be an old neighborhood to deserve and take advantage of their benefits. Doesn’t it strike you as at least somewhat unfair that older neighborhoods have this entire field of law, and world of administrative processes, organized with the goal of protecting their best buildings (and the value of the surrounding real estate) while anything newer, no matter the quality, is left out to dry? Is it any wonder the overwhelming majority of new homes constructed in the past ten years have been located in gated communities with home owner’s associations and deed restrictions?

Americans are probably the last to admit that they would sacrifice the freedom to put plastic flamingoes in their front yard, but more than any other nation in the world we are building and electing to live in places where private governments control everything from lawn furniture to new siding. This trend is nothing less than a cry for architectural regulation, and it’s no coincidence it arose just as suburban sprawl and modern architecture began to consume the landscape. Where the environmentalists have spent all their energy making sure nothing happens to nature, while completely ignoring what gets built, so have the preservationists spent their time obsessing over existing places, and completely ignoring new ones. Both of these positions espouse a hopelessness that leads nowhere.

The truth is that most Americans who live in places that are at all dense—meaning they can see the next house—want some level of guarantee that their neighbor isn’t going to build a neon-colored curiosity that hurts their property values. It’s not unlike the circumstances surrounding the advent of zoning. Though most of the talk surrounding the famous Euclid decision is about the segregation of uses it condoned, the most telling words of the decisions speak of the apartment house in the single family neighborhood as a “pig in the parlor,” which are as applicable to an ugly building as they are to a functionally different one.

The response on the part of preservationists has been to over landmark. What happens is that well-formed neighborhood groups lobby to get their neighborhood designated a historic district. Whether or not it’s the most deserving of places, and whether or not more historic places have yet to be protected, the landmarks commission responds to political pressure. The result is the creation of historic districts all over the city, which have as much to do with out of control new development as they do history. Meanwhile, newer areas that are clearly not ripe for preservation call on the city to downzone their areas to a density much lower than actually exists. The goal being to create an environment where, because of the abnormally low zoning potential, no one will knock an existing building, or build a new one either.

Conclusion

All any of us want, in old neighborhoods or new ones, whether you care about urbanism or not, is a reasonable expectation that what is going to be built will be as good as what it replaces, and some idea what that’s going to look like. Is that so much to ask? These simple objectives are more easily achieved with a code than with a commission; and in the process, we’d be making our approval process more swift, fair, and definite as well.

– – –

Ian Rasmussen is an attorney and urbanist living in New York City. His practice focuses on land use, zoning, and urban design.

[image by Rego-Forest Preservation Council]

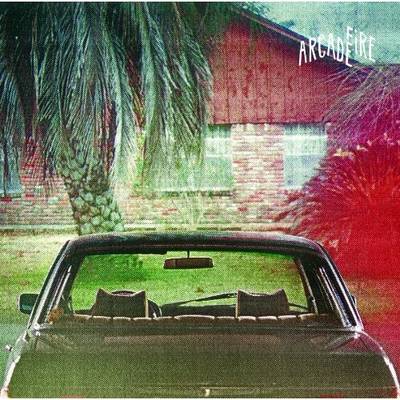

Filed under: Music, Volume 003 | Tags: Arcade Fire, Music, Music Review, Sprawl, The Suburbs, Zack Adelson

The ill effects of sprawling settlements development patterns are well documented. Numerous books, articles, and films have discussed the negative physical, economic and ecological impacts associated with suburban sprawl. However, as a medium for expression, the music industry provides few examples of sufficient coverage. Countering this trend is the band Arcade Fire, whose latest album, The Suburbs, brings to life their own experiences growing up in such an environment. In doing so, they paint an eerie, but accessible picture of what many kids go through growing up in America.

The Arcade Fire is an indie rock band formed in Montreal, Canada by husband and wife duo Win Butler and Régine Chassagne. The group also includes Win’s younger brother, William Butler. Win and Will were born in Northern California, near the Nevada border, in a small rural town. When the brothers were young their family moved to the Woodlands, Texas, a well-known master planned suburb on the outskirts of Houston. The change in scenery was so drastic that Win says “it was like landing on Mars.” What was then an unfamiliar new place sets the stages for the hazy memories that comprise The Suburbs.

The central themes of boredom, confinement, loneliness and regret are brought up repeatedly throughout the album. Some of the most powerful imagery in many of the songs is accompanied by the idea of being lost—Win uses this as a metaphor for feeling afloat in life, with no particular direction. But this sense of confusion is also directly related to the disconnected life he once lived in the suburbs. The point is driven home on the album’s most somber song, Sprawl I (Flatland).

The track describes Win’s return visit to the Woodlands neighborhood where he spent the majority of his childhood. But with so little connection to the place he once lived, he is unable to find the right house. More telling is that during the entire song he deliberately avoids the word “home”. Instead, he searches for “the house where we used to stay.” Towards the end of the track Win recalls being asked by a police officer where he lives. He replies that he does not know but has been searching every corner of the Earth.

Beyond being lost in the sprawl, the Butler brothers also seemed to grow up bored. Many of the songs ring with a tone of regret, recalling summer days wasted indoors, germinating half-baked ideas that were never realized. The listener understands that the brothers did not lack creativity, but simply had no outlet for their talents.

Listening deeper into the album, several songs reference a “suburban war,” a metaphor for childhood fantasies enacted through play. From personal experiences, it could have been a neighborhood wide game of flashlight tag or building a skateboard ramp in the backyard.

“But by the time the first bombs fell

we were already bored

We were already, already bored.”

For the boys the excitement comes in merely talking about their ideas. However, when it came time to see them through to fruition, the motivation runs dry. The disappointment that goes along with discarded plans reveals a sense of impotence, a feeling that makes the suburbs an even lonelier, alienating place.

Among all of the intangible ideas about suburban life discussed on the album, the Arcade Fire offer several hints as to why the Woodlands was such a depressing place to live. In the high-energy track, Month of May, they make a direct reference to automobile-centric planning.

“First they build the road, then they built the town

That’s why we’re still driving around

And around and around and around and around and around and around and around and around”

Similar explanations are heard during the opening presentation of any New Urbanist design charrette.

Towards the end of the album, Chassagne sings about a seemingly post-apocalyptic landscape in the song Sprawl II (Mountains Beyond Mountains). The tune’s subject matter could be lifted straight from the writings of James Howard Kunstler.

“Sometimes I wonder if the World’s so small

That we can never get away from the sprawl

Living in the sprawl

Dead shopping malls rise like mountains beyond mountains

And there’s no end in sight

I need the darkness, someone please cut the lights “

Clearly, The Arcade Fire portray sprawl in a negative light. However, after listening to The Suburbs the question remains: if not low-density, auto-oriented neighborhoods, for what do they advocate?

Surprisingly, the album reveals a mix of feelings towards cities. Indeed, several tracks portray cities as confusing places where people easily lose themselves, while others praise cities as the places where exciting and interesting people live. Ostensibly, the band has grown comfortable with urban living, as they reside in Montreal, one of North America’s most cosmopolitan cities. However, the album reveals that the brothers Butler still long for the soothing calm of their rural birthplace.

When confronted with the question in interviews, Win replies that his goal for the album was to talk about real experiences rather than pretend he grew up in a more edgy, urban environment. The accessibility of the writing is exactly what makes the album so powerful because current and former suburban inhabitants may easily place themselves within each song, making them all the more real and haunting.

– – –

Zack Adelson is a designer and urban advocate currently living and working in Portland, Maine.

Filed under: Economic Development, Urban Planning, Volume 003 | Tags: Bethany Rubin Henderson, Brain Drain, Economic Development, Economy, Human Capital, Jobs, Planners, Public Sector, Ted Wieber III

by Bethany Rubin Henderson and Ted Wieber III

Urban Planning is a public sector occupation. According to the US Bureau of Labor Statistics, nearly 80% of urban planners in the United States work for governments, more than 66% work in local government.1 This fact may not be surprising given the often community-wide impact of planning work, but it means that the health and vitality of the planning profession depends largely on the health of local governments. And right now, America’s local governments are facing a severe talent crisis. While urban planners are comparatively well-off – increasing urbanization in the U.S. will lead to an expected 19% increase in the demand for urban planners between now and 2018 – most other local government sectors are facing a mass exodus of their most experienced workers without a sufficiently large pool of talented replacements to draw from. The fiscal and operational challenges facing cities are more difficult than ever before; yet the brightest minds are in short supply. As this crisis threatens to destabilize local governments across the country, it is more important than ever to aggressively recruit the most talented people to solve our municipal challenges.

The Relationship between Urban Planning and the Public Sector

Many of the most innovative urban planning ideas begin as broad visions devoid of regulatory context: “Wouldn’t it be nice if people could walk more in this part of town?” or “How might we create more vibrant public spaces?” or “How might this community achieve higher usage rates of public transportation?” These are questions that New Urbanists have continuously sought to answer. However, urban planning does not move forward in a regulatory vacuum. The challenge of planning lies in transforming these visions into realities. This metamorphosis can only be achieved through an intimate, and often lengthy, give-and-take with local governments and the people that run them. Like a caterpillar entering its cocoon before being reborn as a butterfly, so a planning vision must weather the halls of city government before emerging as a reality.

Who, exactly, are the people who influence planning at the local level? They include planning department employees, planning and zoning commissioners, building code inspectors, infrastructure engineers, environmental impact analysts, transportation analysts and many others depending on the needs of a particular city, community or project. Beyond the staff directly involved in evaluating proposed development projects, mayors, city managers, council members, and other city officials affect the process by determining local economic policy, property tax rates, and the amounts of impact fees, permit fees, and other fees or taxes that development projects must shoulder. Both elected and appointed city leaders, across agencies, also produce comprehensive community plans, decide the priorities of capital improvement programs, and determine official zoning and subdivision rules.2 Considering the intricate web of regulatory steps that any proposed development must survive, turning a planning vision into a reality can be a herculean task. And that does not even include the outside challenges developers and planners face, like financing a major project.

Moreover, regional, state and federal governments impose constraints on the planning process that can limit the ability of cities to pursue planning initiatives. For example, states and regions often produce transportation plans governing the development of road networks across a region and infrastructure plans with standards for water resources, wastewater treatment, air quality, parks, and transit. State governments and the federal government also control important purse strings. For example, the 2009 American Recovery and Reinvestment Act made enormous sums of money available to state and local governments for “shovel-ready” projects. Local officials have to compete for such money, often by meeting detailed Federal criteria and marshaling local political forces. Without competent, proactive and forward-thinking municipal employees, deserving communities can miss out on important financing that can make or break a needed planning initiative.

The point to take away from this laundry list of governmental actors and regulation is that the influence of government workers on the planning process is enormous. And a malfunctioning local public sector can make the job of urban planners extremely difficult – and significantly more expensive – to accomplish. The tangled web of overlapping plans and regulations can only be navigated – and reformed – by a vibrant and talented supply of knowledgeable local government workers across all fields.

The Aging Workforce

Unfortunately, America’s city governments face a talent crisis. Although the planning sector is expanding, the majority of local government administrators – not the politicians, but the people who do the day-to-day work that keeps cities running and public services on track – either could retire today or will become eligible for retirement within the next five years.34 This looming personnel exodus threatens the ability of cities to function.

The aging government workforce is not simply a consequence of the baby boom generation approaching retirement. While only 48% of private sector employees are over 40, a whopping 63.5% of local government employees are.5 Local government employees are, on average, 5-7 years older than their private sector counterparts.6 Furthermore, local government is disproportionately a “knowledge industry” requiring workers with specialized education, training or skill sets. Two-thirds of local government employees are knowledge workers; only one-third of private sector workers are.7 Nearly half of public sector employees have college degrees, versus fewer than one-quarter of private sector employees.89 Age and education levels almost twice those of the private sector illustrate that the personnel challenges facing government workforces are more serious than those of other job sectors. Interestingly, an aging government workforce is not solely an American challenge. Thirteen member countries of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) have public sectors where workers 50 or older comprise 30% or more of the total workforce.10

If left unchecked, the consequences of an aging municipal workforce could be devastating. First, in a few short years there simply will not be enough people to do the job. Even accounting for the inevitable downsizing and shrinking head-counts that will be lasting effects of the recession, the out-migration of experienced baby boomers will leave numerous vacancies – far too many to be filled by the existing pipeline of talent entering local government. Without adequate staff, cities will not be able to function, much less be efficient and effective stewards of public resources. While an occasional shake-up of the status quo has benefits, the current disruptive human capital crisis threatens consequences that only the skills and innovative thinking of America’s brightest talent can overcome.

Second, an outflow of experienced personnel may lead to the permanent loss of institutional knowledge. The lessons learned and experience acquired after decades of public service are extremely valuable, as relationships and job-specific expertise can only be built over time. Loss of that institutional memory will significantly weaken the knowledge base of municipal agencies. Now that so many government employees are nearing retirement, the threat of a devastating “brain drain” is becoming an imminent reality.

Third, the aging workforce threatens to topple government finances. Municipal budgets across the country are under enormous pressure. The decline in tax revenues due to the recession can be blamed for some of the trouble. However, the long-term strain on municipal budgets comes from pension and benefit obligations promised years ago. Americans are now living longer than ever. Government workers who retired over the past few decades, and those who will retire in the next few, will draw on their pensions and health benefits for much longer than cities budgeted for.11 Besides consuming increasingly large shares of municipal budgets, these pension obligations limit governments’ flexibility to address all of their other responsibilities. To meet their obligations, local governments will have to continue to cut services, shrink programs, and defer or abandon new initiatives. Furthermore, strained budgets could result in cost-shifting from the public to the private sector, driving up the costs of a project for private sector planners and developers.12 Planners – who must inevitably work closely with local governments whether they are employed by them or not – will find cities more financially strapped and inflexible than ever before.

Where are all the young people?

But perhaps the most alarming aspect of the talent crisis is the absence of young college-educated workers in the municipal pipeline. Americans need the same caliber of people in local government who traditionally join top-tier law firms, consulting firms, investment banks, Teach for America and other high-profile or high-profit careers. For decades, America’s best and brightest college graduates have spurned local government service, leaving talented younger workers in short supply. Moreover, recession-driven layoffs – which, in the public sector often favor seniority over performance – are exacerbating the problem by forcing out many of the youngest workers that currently are in the pipeline.13

There are many reasons why young college graduates avoid municipal jobs. First, most college students know little about what government workers actually do, and the little they do know worries them. Many equate working in government with either being a politician or being stuck in an inflexible bureaucracy and endless red-tape.1415 Today’s younger workers want to work in meritocracies that value innovation and creativity and provide opportunities for continuous learning. They crave positions that challenge them, where they can be partners in the enterprise from day one, and that provide a good work-life balance.1617 Few think of municipal agencies as providers of this environment.

Second, a pervasive, decades-old anti-government bias turns off many young Americans from considering government work, even those inclined towards public service.18 Indeed, the 2009 National Leadership Index from Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government found that Americans have a below-average level of confidence in local government.19 Further, when asked to estimate the inefficiency of local government, Americans believed that local governments waste more than 36 cents of every tax dollar they collect.20 Young people also connect “public service” with working for non-profits – not working in government.21

Third, young people simply are not being asked to join government.22 Worse, many city governments’ civil service rules make it nearly impossible for people right out of college to join their workforce by requiring several years of experience for entry-level jobs. Compounding the problem, college graduates now can, and frequently do, move around freely to chase opportunity. Being less rooted in their local communities discourages them from investing time and effort in tackling local challenges.

Finally, public sector compensation packages do not meet the needs of younger workers.23 Local governments pay knowledge workers 25% less than the private sector, and the public-private sector pay gap has grown in the past 15 years.2425 This makes it even harder for cities to recruit and retain the highly-skilled professionals who comprise so much of their workforce – including many who impact the planning process, like engineers and environmental scientists.26

Despite these challenges, engaging recent college graduates in local government is not impossible. Doing so simply requires re-imagining how we inspire and empower them to solve local problems. In fact, public attitudes are shifting, and today we have a unique chance to re-focus our top young people back to the local level. Many 18-30 year-olds now report that doing good for society is as important to them as doing well financially. As importantly, the reflexive anti-government sentiment among young people is decreasing for the first time in decades.2728 A January 2010 Gallup poll found that, while 59% of Americans age 18-30 still prefer working for a business over working for the government, 37% now favor government jobs. Further, 42% of college students now agree that getting involved in politics is honorable.29

What does all of this mean for Urban Planners?

A combination of trends is launching urban planners to the forefront of civil society. First, America is growing rapidly. Demographers forecast the national population will grow to more than 400 million by 2050.30 Second, America is increasingly urbanizing. The Brookings Institution predicts that nearly 90% of Americans will live in metropolitan areas – cities of 50,000+ and their economically-dependent adjacent counties – by 2030.31

Third, there is a renewed emphasis in America on finding local solutions to social problems. Cities are now being placed front and center in the public conscience. How creative urban planning can improve the quality of daily life, public health, and the environment are goals receiving significant attention. Even mainstream media is rife with praise for the social benefits of experimental urban renewal initiatives like New York City’s conversion of Times Square traffic routes to pedestrian thoroughfares, or Stockholm’s bid to make physical activity fun with its “piano stairs.”

In a nutshell, our growing and increasingly urbanized population will place greater stress on municipal services and infrastructure—creating a stronger demand for the expertise of urban planning professionals. It should be no surprise, then, that the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics predicts that the number of urban planning jobs will increase by a startling 19% between 2008 and 2018, a faster-than-average occupational growth rate.32

This growth might be welcome news to professional planners, but it poses a serious challenge to local governments. Not only do cities lack bench strength among their non-planning staff, most also lack viable long-term succession and recruitment plans.3334 Combine an increased demand for city services, a mass exodus of experienced workers and a lack of incoming talent, with no plan for how to deal with this challenge, and you have a perfect storm. Urban planners are caught right in the middle. Weakened local governments translate into a weakened support-system for urban planning initiatives.

One Solution to Attract the Best

Our national, non-partisan nonprofit, City Hall Fellows, offers one solution to the personnel challenges facing local governments. City Hall Fellows has found an effective, cost-efficient and highly-impactful way to convert college students’ renewed interest in public service into their taking responsibility for the challenges in their hometowns. Partnering with city governments, City Hall Fellows runs a Teach-for-America-style national service corps program that includes more than 300 hours of training on local government policy – how decisions are made, how local policy is designed and implemented, and how programs are evaluated. The year-long, cohort-based Fellowship integrates this intensive training with hands-on, full-time professional experience working on substantive projects for city agencies.

City Hall Fellows puts America’s best and brightest recent college graduates to work directly on many of the challenges cities face – including many of the challenges affecting urban planners. For example, a recent Fellow served in the Houston Planning and Development Department. His mission for the year: tackling the problem of institutional memory loss in his department. As the largest city in the United States without zoning, Houston has a very unique approach to regulating planning. In the absence of a zoning ordinance Houston utilizes a variety of stand-alone nuisance ordinances that curb the most egregious land-use incompatibilities while preserving the enormous development flexibility that comes from limited regulation. His work was a key component of a forward-looking department initiative led by senior management to arm current and future planners with knowledge of the department’s past. A comprehensive historical review of Houston’s development ordinances – why the city passed them, how they have been amended over time, and the kinks that may still exist in their implementation – will allow the department to preserve and learn from its history and from the experience of its most senior employees, even as they retire.

But City Hall Fellows alone cannot prevent the potentially devastating blow to our cities – or to occupations like urban planning that depend on cities’ efficacy – from the enormous municipal talent crisis.

What else can be done?

Most importantly, governments must recognize and prioritize their personnel challenges and place greater emphasis on recruiting and retaining new talent. First, cities must overhaul hiring and recruitment practices by removing unnecessary barriers to entry for promising talent. For example, the City of Houston currently requires three years full-time experience for many entry-level positions. This rule effectively precludes top graduates from Houston’s six major universities from working for the city right after college.

Second, the public sector needs to market itself more effectively to college students. While strained municipal budgets may preclude offering pay packages on par with the private sector, public sector workers still enjoy benefits that can more than compensate for the cash discrepancy. For example, young public sector employees get to work at the cutting edge of public policy – and have a real impact on their communities. Likewise, in many cities, public sector workers enjoy more flexible working hours and more paid vacation days than their private sector counterparts.35 As noted above, recent polls show that this combination of intellectually stimulating work that directly impacts the public good combined with generous non-cash benefits is very appealing to today’s college students. Yet, few college students know that local government employment offers these opportunities. Cities can go a long way towards solving their brain drain problem simply by raising college students’ awareness of what working for cities is really like. Social media platforms allow cities to cost-effectively reach tens of thousands of prospective new college-age workers.

Third, senior city workers should actively ensure that their knowledge and experience is not lost. Before retiring, they should document the most vital institutional memory. They should also mentor younger employees in their agencies, preparing them for leadership. Finally, public sector urban planners, ordinary citizens and private sector workers must realize that the municipal talent crisis directly impacts their livelihoods: professionally, financially, and in the quality of service that their government can provide. While private corporations are responsible to their owners and stakeholders, the public sector can only be held accountable by an informed and engaged citizenry. All of us have a responsibility for ensuring our cities continue not just to function, but also to effectively and efficiently serve our needs. An awareness of the talent crisis local governments face must be translated into momentum for the innovation and restructuring required to ensure a healthy future for America’s cities.

Conclusion

Left unchecked, cities’ human capital crisis could undermine even the best-laid urban plans. Talented and innovative people are the key to solving governments’ most intractable problems.

Awareness of the brain drain plaguing the public sector – and consequently the urban planning profession – is slowly growing. But, for change to happen, the chorus needs many more voices clamoring for reform. Urban planners in particular, as an occupational group overwhelmingly concentrated in the public sector, must be on the front lines of this campaign. Planners must demand that their municipal governments prioritize the talent crisis and address it as swiftly as possible; and they must be willing to partner with local governments and non-profits like City Hall Fellows to incentivize talented younger workers to enter public service. Without a steady pipeline of talented workers who can think more creatively than ever before about municipal government’s challenges and how to solve them, the future of America’s cities looks bleak.

SOURCES

Armah IV, Niiobli, et al. “Making Public Service Accessble: Opportunities to Improve the Hiring Process for Our Next Generation of Municipal Employees.” A Report by the Houston City Hall Fellows, July 22, 2009.

Barrett, Katherine & Richard Green. “An Unproductive Bump.” Governing, April 1, 2010 http://www.governing.com/columns/smart-mgmt/An-Unproductive-Bump.html

Bender, Keith A. & John S. Heywood. “Out of Balance? Comparing Public and Private Sector Compensation over 20 Years.” Report commissioned by the Center for State & Local Government Excellence and the National Institute on Retirement Security. April 2010

Benest, Frank, Ed. “Preparing the Next Generation. A Guide for Current and Future Local Government Managers.” International City/County Management Association, 2003.

Benest, Frank. “Retaining and Growing Talent: Strategies to Create Organizational ‘Stickiness’.” ICMA’s PM Magazine. Vol. 90, No 9, October 2008. http://www.frankbenest.com/ICMA%20article.pdf

Bilmes, Linda and W. Scott Gould. The People Factor: Strengthening America by Investing in Public Service. Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution Press, 2009

Council for Excellence in Government. “Calling Young People to Government Service: From ‘Ask Not…’ To ‘Not Asked’.” a Peter D. Hart Research Study for the Council for Excellence in Government, March 2004.

Council for Excellence in Government & the Gallup Organization. “Within Reach . . . But Out of Synch: The Possibilities and Challenges of Shaping Tomorrow’s Government Workforce.” updated May 22, 2007. Retrieved May 20, 2010 from http://www.hreonline.com/pdfs/06162007Extra_GovernmentStudy.pdf

Dohrmann, Thomas, et al. “Attracting the Best.” McKinsey and Co Transforming Government. Autumn.2008. http://www.mckinsey.com/clientservice/publicsector/pdf/TG_attracting_best.pdf

Economist. “A tough search for talent.” 31 Oct 2009.

Franzel, Joshua M. “Future Compensation of the State and Local Workforce.” http://www.thepublicmanager.org. http://www.slge.org/vertical/Sites/{A260E1DF-5AEE-459D-84C4-876EFE1E4032}/uploads/{2861CCEA-7045-4C8D-86F0-1C5323204D17}.PDF

Gallup Government Poll, 2009. http://www.gallup.com/poll/27286/Government.aspx

Greenfield, Stuart. “Public Sector Employment: The Current Situation.” Center for State & Local Government Excellence, 2007, http://www.slge.org/vertical/Sites/{A260E1DF-5AEE-459D-84C4-876EFE1E4032}/uploads/{B4579F88-660D-49DD-8D52-F6928BD43C46}.PDF

Henderson, Bethany Rubin. “Don’t Shut the Door on Your Way Out: Stopping the Threat to City Operations Posed by the Aging Municipal Workforce.” 97 National Civic Review 3, p. 3 (Fall 2008)

Kellar, Elizabeth, et al. “Trends to Watch in 2010.” PM Magazine (ICMA Press) Vol. 92, No 1, January/February 2010 (cover story) http://icma.org/pm/9201/public/cover.cfm?author=Elizabeth%20Kellar,%20Joshua%20Franzel,%20Danielle%20Miller%20Wagner,%20and%20Joan%20McCallen&title=Trends%20to%20Watch%20in%202010

Kotkin, Joel. The Next Hundred Million: America in 2050. Penguin Press, 2010.

Levine, Peter, et al. “The Millennial Pendulum: A New Generation of Voters and the Prospects for a Political Realignment.” New America Foundation Next Social Contract Initiative (Feb. 2008). http://www.womenscolleges.org/files/pdfs/Millennial_Pendulum_Feb08.pdf

Miles, Mike E., et al. Real Estate Development: Principles and Process. 4th Edition. Urban Land Institute, 2007.

“National Leadership Index 2009.” Center for Public Leadership, John F. Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University.

Partnership for Public Service. “Poll Watch: Public Opinion on Public Service.” May 2, 2005.

Pew Research Center. “Millenials: A Portrait of Generation Next.” 2010. http://pewsocialtrends.org/assets/pdf/millennials-confident-connected-open-to-change.pdf

Puentes, Robert. “How Are We Growing? Where Are We Going?: How We Will Live and Move in 2050.” Presentation at American Transportation Association. Sept. 19, 2007.

“Survey of Young Americans’ Attitudes towards Politics and Public Service.” Harvard University, Institute of Politics: 17th Edition. March 9, 2010. http://www.iop.harvard.edu/var/ezp_site/storage/fckeditor/file/100307_IOP_Spring_10_Report.pdf

“A Tidal Wave Postponed: the Economy and Public Sector Retirements.” Center for State and Local Government Excellence. May 2009.

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. “2010-11 Occupational Outlook Handbook.” http://www.bls.gov/oco/ocos057.htm

Young, Mary B. “The Aging-and-Retiring Government Workforce: How Serious is the Challenge? What Are Jurisdictions Doing About It?” CPS Human Resource Services, 2003. http://www.wagnerbriefing.com/downloads/CPS_AgeBubble_ExecutiveSummary.pdf

NOTES

1 U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. “2010-11 Occupational Outlook Handbook.”

2 Miles, Mike E., et al. Real Estate Development: Principles and Process. 4th Edition. Urban Land Institute, 2007. Ch. 13

3 Young, Mary B. “The Aging-and-Retiring Government Workforce: How Serious is the Challenge? What Are Jurisdictions Doing About It?” CPS Human Resource Services, 2003. http://www.wagnerbriefing.com/downloads/CPS_AgeBubble_ExecutiveSummary.pdf

4 Henderson, Bethany Rubin. “Don’t Shut the Door on Your Way Out: Stopping the Threat to City Operations Posed by the Aging Municipal Workforce.” 97 National Civic Review 3, p. 3 (Fall 2008)

5 Greenfield, Stuart, Public Sector Employment: The Current Situation, Center for State & Local Government Excellence (2007), http://www.slge.org/vertical/Sites/{A260E1DF-5AEE-459D-84C4-876EFE1E4032}/uploads/{B4579F88-660D-49DD-8D52-F6928BD43C46}.PDF

6 Kellar, Elizabeth, et al. “Trends to Watch in 2010.” PM Magazine (ICMA Press) Vol. 92, No 1, January/February 2010 (cover story) http://icma.org/pm/9201/public/cover.cfm?author=Elizabeth%20Kellar,%20Joshua%20Franzel,%20Danielle%20Miller%20Wagner,%20and%20Joan%20McCallen&title=Trends%20to%20Watch%20in%202010

7 Greenfield, Stuart.

8 Bender, Keith A. & John S. Heywood. “Out of Balance? Comparing Public and Private Sector Compensation over 20 Years.” Report commissioned by the Center for State & Local Government Excellence and the National Institute on Retirement Security. April 2010

9 Greenfield, Stuart.

10 Economist. “A tough search for talent.” 31 Oct 2009

11 Bilmes, Linda and W. Scott Gould. The People Factor: Strengthening America by Investing in Public Service. Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution Press, 2009. (p. 23)

12 Miles, Mike E., ch. 13.

13 Barrett, Katherine & Richard Green. “An Unproductive Bump.” Governing, April 1, 2010 http://www.governing.com/columns/smart-mgmt/An-Unproductive-Bump.html

14 Council for Excellence in Government & the Gallup Organization. “Within Reach . . . But Out of Synch: The Possibilities and Challenges of Shaping Tomorrow’s Government Workforce.” updated May 22, 2007. Retrieved May 20, 2010 from http://www.hreonline.com/pdfs/06162007Extra_GovernmentStudy.pdf

15 Benest, Frank, Ed. “Preparing the Next Generation. A Guide for Current and Future Local Government Managers.” International City/County Management Association, 2003.

16 Armah IV, Niiobli, et al. “Making Public Service Accessble: Opportunities to Improve the Hiring Process for Our Next Generation of Municipal Employees.” A Report by the Houston City Hall Fellows, July 22, 2009.

17 Benest, Frank. “Retaining and Growing Talent: Strategies to Create Organizational ‘Stickiness’.” ICMA’s PM Magazine. Vol. 90, No 9, October 2008. http://www.frankbenest.com/ICMA%20article.pdf

18 Benest, Frank, Ed. “Preparing the Next Generation. A Guide for Current and Future Local Government Managers.”

19 “National Leadership Index 2009.” Center for Public Leadership, John F. Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University.

20 Gallup Government Poll, 2009. http://www.gallup.com/poll/27286/Government.aspx

21 Council for Excellence in Government. “Calling Young People to Government Service: From ‘Ask Not…’ To ‘Not Asked’.” a Peter D. Hart Research Study for the Council for Excellence in Government, March 2004.

22 Partnership for Public Service. “Poll Watch: Public Opinion on Public Service.” May 2, 2005.

23 Franzel, Joshua M. “Future Compensation of the State and Local Workforce.” http://www.thepublicmanager.org. http://www.slge.org/vertical/Sites/{A260E1DF-5AEE-459D-84C4-876EFE1E4032}/uploads/{2861CCEA-7045-4C8D-86F0-1C5323204D17}.PDF

24 Bender, Keith A. & John S. Heywood.

25 Greenfield, Stuart.

26 Bender, Keith A. & John S. Heywood.

27 Pew Research Center. “Millenials: A Portrait of Generation Next.” 2010. http://pewsocialtrends.org/assets/pdf/millennials-confident-connected-open-to-change.pdf

28 Levine, Peter, et al. “The Millennial Pendulum: A New Generation of Voters and the Prospects for a Political Realignment.” New America Foundation Next Social Contract Initiative (Feb. 2008). http://www.womenscolleges.org/files/pdfs/Millennial_Pendulum_Feb08.pdf

29 “Survey of Young Americans’ Attitudes towards Politics and Public Service.” Harvard University, Institute of Politics: 17th Edition. March 9, 2010. http://www.iop.harvard.edu/var/ezp_site/storage/fckeditor/file/100307_IOP_Spring_10_Report.pdf

30 Kotkin, Joel. The Next Hundred Million: America in 2050. Penguin Press, 2010.

31 Puentes, Robert. “How Are We Growing? Where Are We Going?: How We Will Live and Move in 2050.” Presentation at American Transportation Association. Sept. 19, 2007.

32 U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

33 “A Tidal Wave Postponed: the Economy and Public Sector Retirements.” Center for State and Local Government Excellence. May 2009. p. 3

34 Kellar, Elizabeth, et al.

35 Dohrmann, Thomas, et al. “Attracting the Best.” McKinsey and Co Transforming Government. Autumn.2008. http://www.mckinsey.com/clientservice/publicsector/pdf/TG_attracting_best.pdf

Filed under: Urban Planning, Volume 003 | Tags: John Parman, Living Urbanism 003, Planning Process, San Francisco, Urban Planning, Urban Theory, Zoning

View of the Pyramid block from the northeast (along Columbus). The proposed 555 Washington Tower is to the left of the Pyramid.

By John Parman

Early in 2010, San Francisco witnessed another skirmish over density. This one involved a proposal to replace an existing building on the same block as the 48-story, 850-foot-high Transamerica Pyramid (1972). Located at the corner of Sansome and Washington Streets, along the north edge of the Financial District, the proposed 38-story tower considerably exceeded the maximum-height “wall” of 200 feet called for by the City’s current zoning regulations along the district’s north edge.

Dubbed 555 Washington by its backers, a Dutch insurance company and a local developer, the project was hotly debated until April, when the San Francisco Board of Supervisors unanimously decertified its environmental impact report. I wrote a polemical piece for Architect’s Newspaper noting the exceptions to existing zoning the tower would require and suggesting that its approval would put pressure on the much lower blocks north of Washington Street1. I was inspired to write it by a column in the San Francisco Chronicle by the local political commentator C.W. Nevius. He wrote,

This is supposed to be about a debate over erecting a 430-foot condominium tower in the Financial District. But that’s not really true. This is actually a battle for the soul of new San Francisco. That’s not an overstatement. This is the central issue of the emerging, changing city—to build or stall. Detractors have decided to make their stand with 555 Washington St., in the shadow of the Transamerica Pyramid. They’re not just trying to stop a construction project—this is a statement against renovation, new construction, and urban gentrification. They are complaining that the 38-story building is too tall, casts too much shadow, breaks too many planning guidelines and violates the established values of old-time San Francisco.2

Nevius noted that the 200-foot wall was put in place by San Francisco’s 1985 Downtown Plan. “The idea back then was to limit towering office buildings,” he added. “It never occurred to anyone that in 25 years people would want to live downtown.” He quotes Telegraph Hill Dwellers President Vedica Puri: “So they are saying the Downtown Plan is outdated. You know what you have to do then? Redo the Downtown Plan.” This would take years, Nevis argued, urging that 555 Washington be approved. Otherwise, “this project would die, putting a serious chill on any interest in fighting this battle for another development,” he wrote. “And keep in mind, this in an area that hasn’t had significant residential building since the 1980s.”

I agree with Puri. When you remove the current 200-foot height limit along the north edge of the Financial District, what’s at stake is the district that adjoins it. The Downtown Plan didn’t set the height limit to preclude residential development, but to establish a clear boundary. While 555 Washington is 420 feet shorter than the Pyramid, it is 220 feet taller than it should be. Located right at the edge, the Pyramid—completed 13 years before the Downtown Plan—sought to shift the center of gravity of the Financial District north from Market Street, away from transit. The Downtown Plan rejected this, emphasizing the Market-and-Mission corridor as the core of high-density redevelopment in downtown San Francisco. That emphasis was reiterated more recently by the Transbay Terminal Area Plan, which calls for very tall buildings in the corridor.

Nevius is also privileging a “progressive” future against a stagnant present. The opponents of 555 Washington are portrayed as nostalgic, elitist, and out of touch. Although he opposed the tower and called for a new Downtown Plan, the San Francisco Chronicle urban design writer, John King, has expressed a similar view of “reflexive” preservationists. So has the San Francisco Urban Research Association (SPUR), an influential urban policy group in the city.

Place Versus Progress

A question that these arguments raise is whether modern life has left us ill-equipped to consider density in relation to the scale and character of a place. Have we actually been blinded by the assumptions of modernity to disregard what surrounds us and opt instead for “progress” that speaks to abstract values rather than to the actual experience of a city as a series of places?

Reading an interview of the philosopher Ivan Illich3, I came across a reference to Leopold Kohr (1909–1994), a political theorist best known for the phrase, “Small is beautiful.” In a talk that Illich gave at Yale University in October 19944, he noted that Kohr advocated for proportionality rather than smallness. Reading Illich on Kohr’s main themes, I saw his relevance to the question.

Kohr argued that everything that exists has natural limits, and that cities arose and thrived thanks to a widely shared “common sense” about the limits of their pieces and parts, and the ways in which they properly related to each other. Proportionality for Kohr meant “the appropriateness of the relationship.” Another key word for him was certain, as in “a certain way.”

Kohr would say that bicycling is ideally appropriate for one living in a certain place. This statement reveals that “certain,” as used here, is as distant from “certainty” as “appropriate” is from “efficient.” “Certain” challenges one to think about the specific meaning that fits, while “appropriate” guides one to knowledge of the Good. Taking “appropriate” and a “certain place” together allows Kohr to see the human social condition as that ever unique and boundary-making limit within which each community can engage in discussion about what ought to be allowed and what ought to be excluded.

In other words, we cannot meaningfully discuss density except in relation to a certain place. The question density poses is, “What relationships are appropriate to that place?” It’s not a question which is meant to be posed or discussed in abstract. “Who is the community?” is also a relevant question: in relation to a certain place, “community” is no abstraction, either. In his talk, Illich noted that, with the Enlightenment, we began to lose our grasp of proportionality in this sense.5

A Loss of Specificity

“Plato would have known what Kohr was talking about” Illich said. “In his treatise on statecraft he remarks that the bad politician confuses measurement with proportionality.” He goes on to note how words like ethos, paideia, and tonos, which implied “proportion as a guiding idea, as the condition for finding one’s basic stance,” were either lost or took on new meanings during the period of the Enlightenment.

This disappearance has hardly been recognized in cultural history. The correspondence between up and down, right and left, macro and micro, was acknowledged intellectually, sense perception confirming it, until the end of the 17th century. Proportion was also a lodestar for the experience of one’s body, of the other, and of gendered relations. Space was simply understood as a familiar cosmos. Cosmos meant that order of relationships in which things are originally placed. For this relatedness—this tension or inclination of things, one to another, their tonos—we no longer have a word. Tonos was silenced in the course of Enlightenment progress as a victim of the desire to quantify justice. Therefore we face a delicate task: to retrieve something like a lost ear, an abandoned sensibility.

Another word Illich mentions is temperament. “To temper was to bring something to its proper or suitable condition, to modify or moderate something favorably, to achieve a just measure,” he explains. At the beginning of the 18th century, though, it took on a new meaning: “to tune a note or instrument in music to fixed intonation.” Music strove for universality in this shift, leaving its roots in the local and specific, an impulse with parallels across Enlightenment-influenced culture. “Proportionality being lost, neither harmony nor disharmony retains any root in ethos,” he says. “The good, Kohr’s certain appropriateness, becomes trite, if not a historical relic.” The result is a shift from “the good” to “values” as the rise of science changed the nature of language:

An ethics of value—with its misplaced concreteness—allowed one to speak of human problems. If people had problems, it no longer made sense to speak of human choice. People could demand solutions. To find them, values could be shifted and prioritized, manipulated and maximized. Not only the language but the very modes of thinking found in mathematics could norm the realm of human relationships. Algorithms “purified” value by filtering out appropriateness.

Modernity, that child of the Enlightenment, came with a price. The prestige of science meant that scientism entered the rest of life. How we think and talk about density today, and how we try to regulate it, is symptomatic of this. Much urban development is a diktat of abstract values, higher density for its own sake, which refuses to see the existing cityscape as being a “good” in itself.

A Plea for Tonos

“In matters of the heart, we acknowledge an abiding uncertainty,” said the writer Siri Hustvedt. Ordinary people express their desires, and desires are ambiguous, she went on to note.6 The East German activist Bärbel Bohley, describing her disappointment in German reunification, said, “We wanted justice and we gained the rule of law. Our society was never speechless or dumb. That was only in public. Problems were discussed around every kitchen table—much more than they are today.”7 Leaving room for ambiguity is hard when density is reduced to an abstraction. Discussing it around the kitchen table is hard when ordinary people are viewed by experts as an obstacle to progress. Perhaps we could say, with Illich and Kohr, that modernity itself has left us without sufficient specificity about the cities we inhabit to discuss their density meaningfully.

Not every planner is proportion-blind, as Kohr and Illich might put it, but the justification for density in urban settings often takes leave of nuance, cutting itself off from the qualities of place that are reflected in the existing urban fabric. The question to ask of density is, “What will it actually contribute to this place—this site, block, neighborhood, or district—in terms of livability, urbanity, and sustainability?” To answer it, we need to restore a “common sense” about proportionality and appropriateness, so that the subject of density regains moorings to actual settings and to those who live and work in them.

This is not to say that the existing fabric should simply be replicated at its current scale. That’s too often the argument on the other side: Leave it as it is! Kohr and Illich are not making that argument, but suggesting that there is a potential common ground between the two poles of applying abstract regional density targets, on the one hand, and resisting urban redevelopment, on the other. However, there is also massive distrust across that divide. On both sides, bridging the gap means finding a shared language about the evolution of our cities that honors the heart as well as the head, restoring tonos and common sense—temperament in its older sense.

The ends are worth these means. Without substantive, ongoing, community-based debates about our cities as a series of real places, we’re not as smart about their development as we need to be. What’s at stake is our cities’ urbanity—now and in the future. Behind urbanity are the place-specifics of proportionality and appropriateness. And behind them are the people who care about these places, sometimes with the irrational ardor of lovers. Planners should be among them.

Notes

- John Parman, “Urbanity, not just Density,” Architect’s Newspaper, California edition, March 31, 2010, page 22.

- C.W. Nevius, “Tower new front line in fight for S.F.’s future,” San Francisco Chronicle, February 13, 2010. The quotes from Nevius that follow are from this article.

- David Cayley, “Introduction,” Ivan Illich in Conversation, Anansi, 2007, pages 15–16.

- Ivan Illich, The Wisdom of Leopold Kohr, 14th Annual E.F. Schumacher Lecture, Yale University, October 1994, E.F. Schumacher Society, 1996. The other quotes are from the lecture, which was republished by the Schumacher Society as a pamphlet.

- Words like proportionality are being used here in their pre-Enlightenment sense.

- Siri Hustvedt, “A Plea for Eros,” Yonder, Henry Holt, 1998, page 90.

- The first sentence is from “Bärbel Bohley,” The Economist, September 25, 2010, US edition, page 107; the rest from Quentin Peel, “Bärbel Bohley, East German dissident, 1945–2010,” Financial Times, 25–26 September 2010, US edition, page 5.

John Parman writes for Arcade, arcCA, Architect’s Newspaper and other publications, and co-founded and published the journal Design Book Review (1983–1999). He lives in Berkeley, CA.

Filed under: Commerce & Retail, Volume 003 | Tags: Commerce & Retail, Living Urbanism, Retail, Seth Harry, Smartcode

By Seth Harry, AIA, CNU – October 6, 2010

Historical Background

Emerging coincidently with the advent of agriculture, urbanism—a tool for maximizing the value of limited resources through spatial efficiencies and the effective leveraging of collective skills— is one of mankind’s greatest and most enduring inventions. The surplus production and storage of food that agriculture provided encouraged stability and allowed for both specialization and the systematic exchange of goods and services on a localized basis. This, in turn, led to the creation of a rational framework of land division and individual access based upon formal geometric relationships that have proven remarkably consistent across both geographical and generational divides: The long-gone residents of Pompeii—the Roman-era town frozen in time by volcanic eruption 2,000 years ago—would have felt right at home as contemporary inhabitants of Antigua de Guatemala, a vibrant, colonial-era New World capitol, and vice-versa.

This continuity of form and function over the centuries is no accident. Specialization and the division of labor encouraged the development of more complex and robust systems from which modern civilization emerged, including efficient social and production networks optimized around the unique features and indigenous resources found within the regions in which these settlements formed. As a complex dynamic system for human habitation, urbanism shares many attributes and characteristics with natural ecosystems in the sense that the competitive checks and balances within the collective enterprise, by nature, work toward maximizing efficiency and resource utilization over time. This system is enhanced and facilitated through the physical characteristics of the built environment itself. The result is a sustainable model in which the value and usefulness of the output routinely surpasses that of the collective inputs, such that a progressively higher quality of life is consistently realized over time.

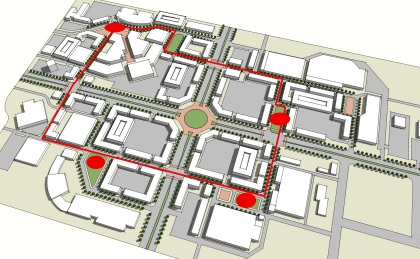

Once the basic framework of urban form was established, the competing dictates of access, capacity, and mobility quickly generated the basic format that emerged— a contiguous network of small-scale blocks and streets. The desire for frontage (width), balanced against the need for capacity (depth), and the shared interests of collective mobility tempered both, keeping block dimensions to a minimum in size, facilitating movement across the fabric. This archetypal form has remained relatively unchanged over the millennia that followed, and continues to prove its relevance to this day.

Over time, these individual settlements typically coalesced within a regional context into semi-autonomous economic constructs, which translated agrarian, craft, and cultural traditions into a coherent set of principles and practices through which the local trade in goods and services could be effectively managed over time. Prior to the industrial revolution, this approach generally encouraged a sense of stewardship toward the land which promoted long-term sustainability through the carefully managed use of local resources, and shared assets, in a largely agricultural-based economy.

As these regions matured, and the scale and nature of local production increased to encompass a broader range of consumer goods, these products were typically distributed and marketed within the community through an efficient network of small-scale merchants and entrepreneurs relying primarily on locally sourced goods for inventory, and tied closely to the physical and spatial structure of the settlements they served.

This model was not only inherently efficient, it also internalized local consumer spending in a systemic fashion which recycled the value of those purchases many times over throughout the local economy. This, in turn, helped ensure a stable and prosperous community, supported by a largely self-sustaining economic system that could operate independently of extra-regional economic trends and developments.

The Modern Era

Beginning in the early Twentieth century, this systemic model of localized production and consumption began to change. Innovations in mechanized transport expanded the reach of urban cores, as the promise of personal mobility on a mass scale precipitated the first substantive break from the established geometric and spatial patterns of the previous four thousand years. As documented in the analysis of neighborhood street patterns, by Michael Southworth and Peter Owens, the enhanced mobility provided by the automobile began to subtly change settlement patterns and their associated road networks, over the course of the 20th century. Their diagram shows a progression of street network types from the traditional “gridiron” of 1900, through “fragmented parallel” circa 1950, proceeding through “warped parallel” (c1960), “loops and lollipops” (c. 1970), and finally, “lollipops on a stick” (c. 1980), the latter representing a 70% reduction in connectivity, from the original grid configuration. As it became both feasible, and more marketable, to segregate uses and residential product types from one another into physically discrete pods, or sub-groupings, this trend toward income stratification and spatial isolation was further exacerbated.

Characterized by ad-hoc, “leap-frog” development, these new large-scale subdivisions and so-called planned communities fully exploited these newly articulated class distinctions, and became the dominant new model of growth in the last half of the last century, the cul-de-sac its increasingly ubiquitous symbol.